On self-imposed constraints

How the act of enforcing rules can pave the way for creativity and ingenuity in Alphabetical Diaries and Bluets

A few weeks ago, I attended an event in Brooklyn for the launch of Sheila Heti’s new book called Alphabetical Diaries. She was in conversation with Lillian Fishman about the book that would be released the next day. I had read her books Motherhood and Pure Colour and fell in love with her stimulating, existential thinking and writing.

But this book was different from the novels she’s known for. For this one, Heti collected all her diary entries since 2005, imported them into a spreadsheet, separated them by sentence, and alphabetized those sentences. From this database of half a million words, she trimmed and trimmed–never adding or rewriting, her cardinal rule–to create a memoir telling the story of her inner most thoughts and the plot of her life not chronologically, but alphabetically. She recontextualized decades of her life line by line. She took this massive block of clay and sculpted it into a finite, 213-page work of art.

During the event, she was asked about process (she started from scratch multiple times), recurring themes in the book (sex and avoiding writing as the top contenders), which letter was the hardest to crack (‘I’ because aren’t we all selfish creatures?)

She outlined her self-imposed rules for the years-long process and discussed the beauty and pain of working with–or more so, within–them. She saw these rules as a game: stumbling upon the happy accident of one sentence flowing perfectly into the next, unrelated one and making ruthless decisions about what to keep and what to lose.

The shaping and editing of this book became a respite from her other work: books and pieces that lacked clearly defined rules. She expounded on the pressure that comes with writing books and how this project became a safe space to experiment and mess around, offering the levity of method that was missing in her novel writing process.

The NYT Book Review says of the book: “I liked the way this book’s format stripped her prose, and her concerns, down to the DNA. Heti has written a small classic; she has shot a lasting arrow into the hide of the memoir form. While reading I began to dream about finding someone to arrange some of my favorite books.”

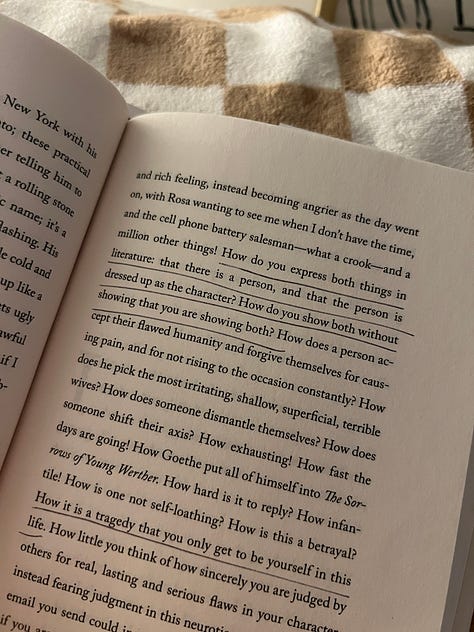

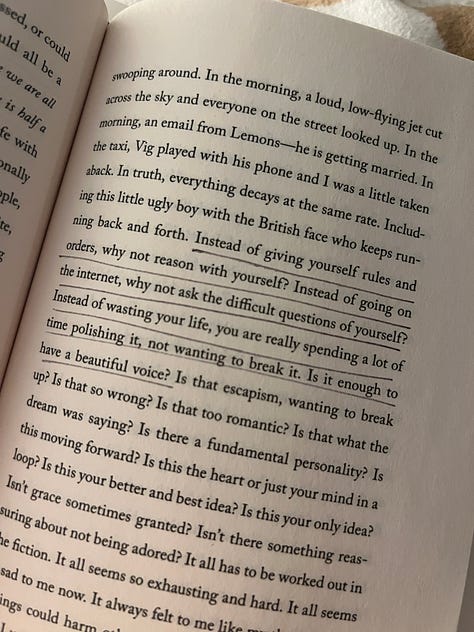

Reading this book is a baffling experience because the unorthodox context of how it was created was constantly floating in the back of my head, at odds with the words that were coherent and beautifully written on the page. The book is thought-provoking and tangibly inspiring in a way that’s different from any book I’ve read before–what would it look like for all of us to do the exercise of alphabetizing our deepest, most private thoughts? Or like the review says, even our favorite books?

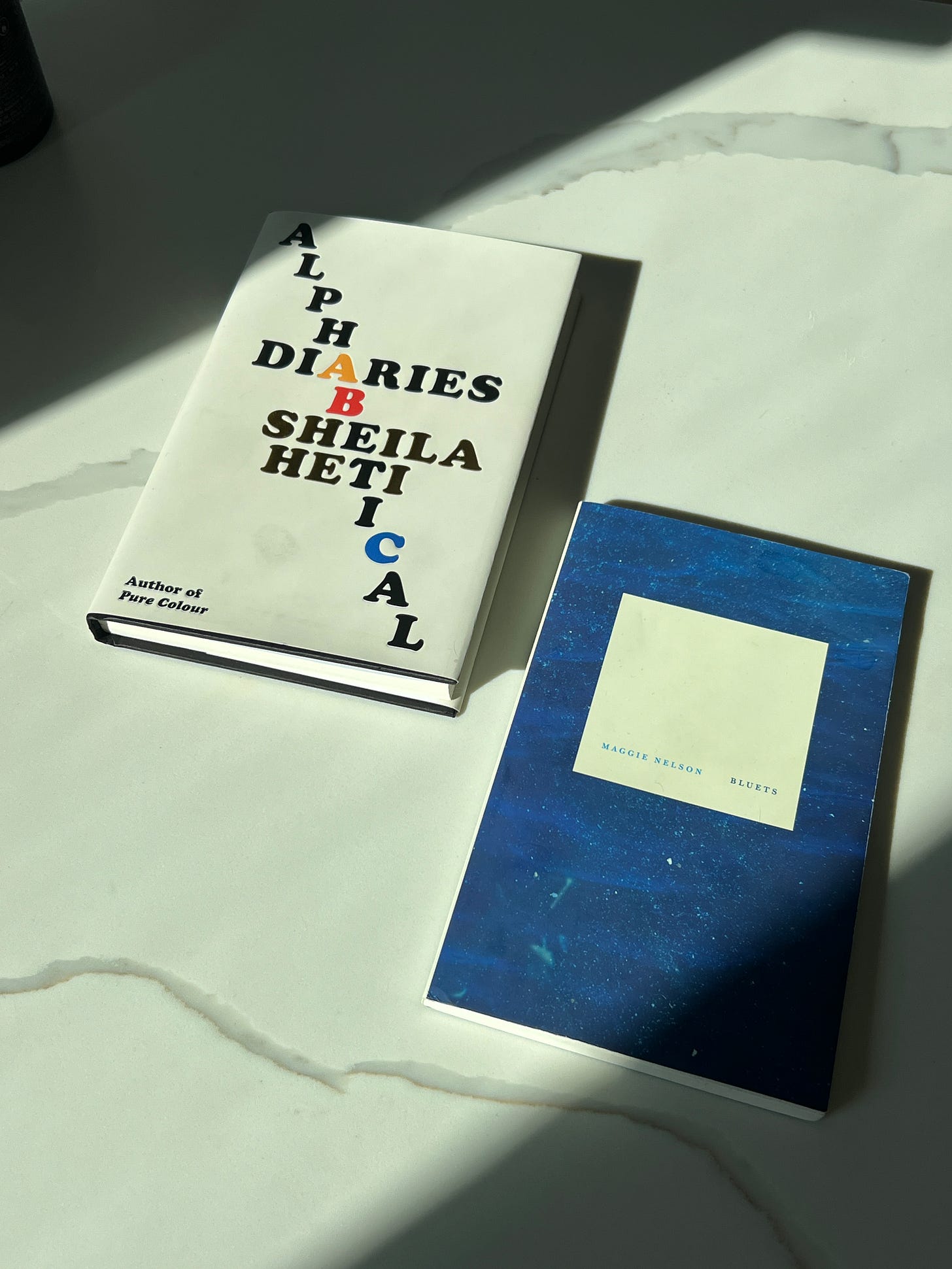

About a week later, I picked up Bluets by Maggie Nelson. Bluets is a memoir in the same way Alphabetical Diaries is: it tells the story of a person’s life experience, but in a way that is seemingly unrelated and wildly unique all the same. In the book, Nelson creates a collection, a linguistic mood board if you will, of the color blue. She curates blue-related fragments and personal stories and anecdotes and “propositions” as she calls them.

“At the bottom of the swimming pool, I watched the white winter light spangle the cloudy blue and I knew together they made God.”

“Indigo makes its stain not in the dyeing vat, but after the garment has been removed.”

“And so we arrive at one instance, and then another, upon which blue delivered a measure of despair. But truth be told: I saw them as purple.”

Over the course of three years as she trudged through the depths of depression, she found solace and light in her love of the color, and in the process of collecting it. She says “the book was my way of making my life feel ‘in progress’ rather than a sleeve of ash falling off a lit cigarette.” The focus required in staying true to the concept kept her going, a fierce commitment to blue.

Reading these two books in quick succession had me pondering the idea of self-imposed constraints, of giving yourself rules to follow, guidelines to work within when creating.

Rules are an inherent facet of the experience of being a functioning person in society. They exist to bring order to chaos. They take all the possible actions, situations, choices that could occur and exclude, declaring what’s allowed and what’s not. Thoroughly intertwined with power, rules are rooted in and can be intended for good or evil, depending on who you ask.

But sometimes to disobey, to go against the grain, against The Man, to rebel–that can be a lot more fun. As Heti said herself during the event, “Anything without rules is better than something with.” Rules are seen as limitations and restrictions, and who would want to be inhibited when you could be free?

But what if we think of certain rules like a prompt, an assignment to answer to, a challenge to face? What if we can wield them as a tool with which to create?

Constraints—time, money, resources, parameters, the list goes on—can lead you to solutions otherwise unseen. They can pave a way, create a sandbox.

Writing the story of twenty years of a life like in Heti’s book or about big, meaty concepts like love and grief in Nelson’s can be difficult to do head-on. To sit down and just write with an intention that big can be paralyzing. In these cases, ‘alphabetizing’ and ‘blue’ narrowed the lens to provide new opportunity for creativity, as evidenced in the final work. A guiding principle simplifies the daunting task of staring at a blank page. Heti said it made it feel more like a game. What seemed like it could box these artists in—guardrails of any kind—is what set them free.

It’s fascinating how, sometimes, the stricter the guidelines, the more “experimental” the outcome is. Heti talked about how her book lived in three different genre sections in bookstores across the US, UK, and Canada. Alphabetical Diaries simply can’t be tied down.

Experimental fiction is a whole other rabbit hole in which I only dipped my toe in to write this, but the thesis remains. In a LitHub article by experimental fiction writer Marisa Crane, she says “using inventive forms and styles to tell stories isn’t about doing what’s never been done before—it’s about stretching the limits of storytelling … Having a structure in mind before you get started experimenting can be very helpful for providing you with a template or framework in which to tell your story. A template can be very freeing and offer space for free-associating because you already have a basic outline for the piece, which means you can go wild within those constraints.”

Billie Eilish and Finneas were facing a brutal bout of writer’s block when Greta Gerwig asked them to write a song for the Barbie movie. In interviews, she’s talked about how they had been attempting to work on her next album for weeks to no avail. They were uninspired—the task of sitting down and writing a song about anything at all was too much. But when given the brief of writing “Barbie’s heart song”, when asked to–or given permission to–focus, to drown out the noise of endless possibilities, to think through the lens of someone or something else, they found their answer. It gave her the path to tell her own truth.

I Hope This Finds You Well is a book of poetry by Kate Baer. She takes hate comments from social media and blacks out certain words to create poetry with an entirely different message. This concept, the constraint of starting from a foundation of negativity, only working from the material provided, allows her to turn evil into love, hate into joy through selective removal. A lot of poetry in general is built from rhythmic and syllabic constraints, too.

How the Word is Passed is another one that comes to mind—a phenomenal book. Clint Smith identified multiple locations with a storied history of slavery, visited them, and let the story unfold from there. The rules, in this case, concentrated the research. The requirements baked into the experience of writing this project is what allowed for personal beliefs and revelations to bubble up throughout it.

There are countless examples of constraints breeding creativity. One could argue everything is informed by rules in one way or another, but in Alphabetical Diaries and Bluets, the constraint provided the backbone of the book. The form was the function, and the authors made beautiful meaning out of both.

The rules they declared for themselves while writing seem to have held their hand along this personal journey. Their respective structures acted almost as a bodyguard, shielding and guiding them along their quest to navigate and reflect on the big, scary things that make up this life in a manageable, bite-by-bite way. In both books, it’s clear the act of writing through that lens helps them, soothes them, heals them.

So when the world feels like it’s too much, maybe it’s time to put some rules in place and see what happens.

See you in a few days for the February roundup!