Paris & its literary lifeblood

A wander through Paris' Left Bank in the early 20th century, and the writers that made it magical

A couple weeks ago, I went to Paris with one of my besties. We drank wine, ate snails, and watched fabulous French people live their lives.

Because I’m me, and Paris is Paris, I couldn’t help but think of all the fascinating literary history baked into the streets and balconies and spirit of the city.

I swiftly fell down the rabbit hole—join me…

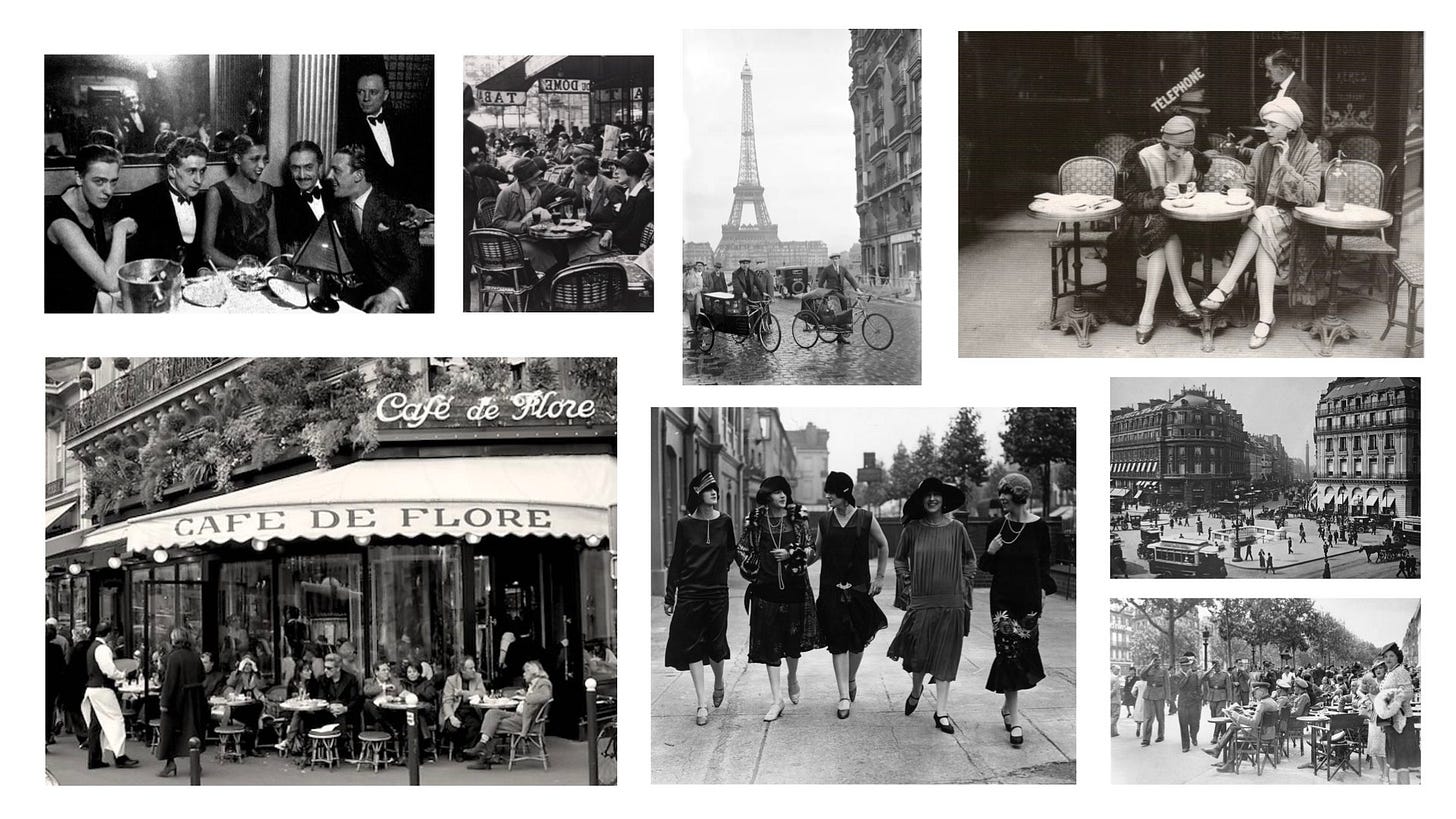

There’s something in the air of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

You can feel it now, and I’m certain—by certain I mean, I’ve watched Midnight in Paris—you could feel it a century ago. The concentration of writers, painters, artists, creatives, that converged in the half-mile radius of this neighborhood during this time is mind-boggling. It seemed… electric.

But before Hemingway or Joyce stepped on the scene, the groundwork was being laid for the city of love to become a mecca of expression and creativity. And who laid that groundwork you ask? Some iconic women that’s who.

Or “New Women” as the particular flavor of feminism was called at the time, the term coined in 1894. New Women were basically just… empowered women. Those with an independent spirit, an intellectual pursuit, and desires all her own. As the nineteenth century turned to the twentieth, women were becoming much freer (it’s all relative) than they were in the Victoria era before. Paris—its imagination and inspiration—expanded their minds and encouraged them out of the shell the times forced them into.

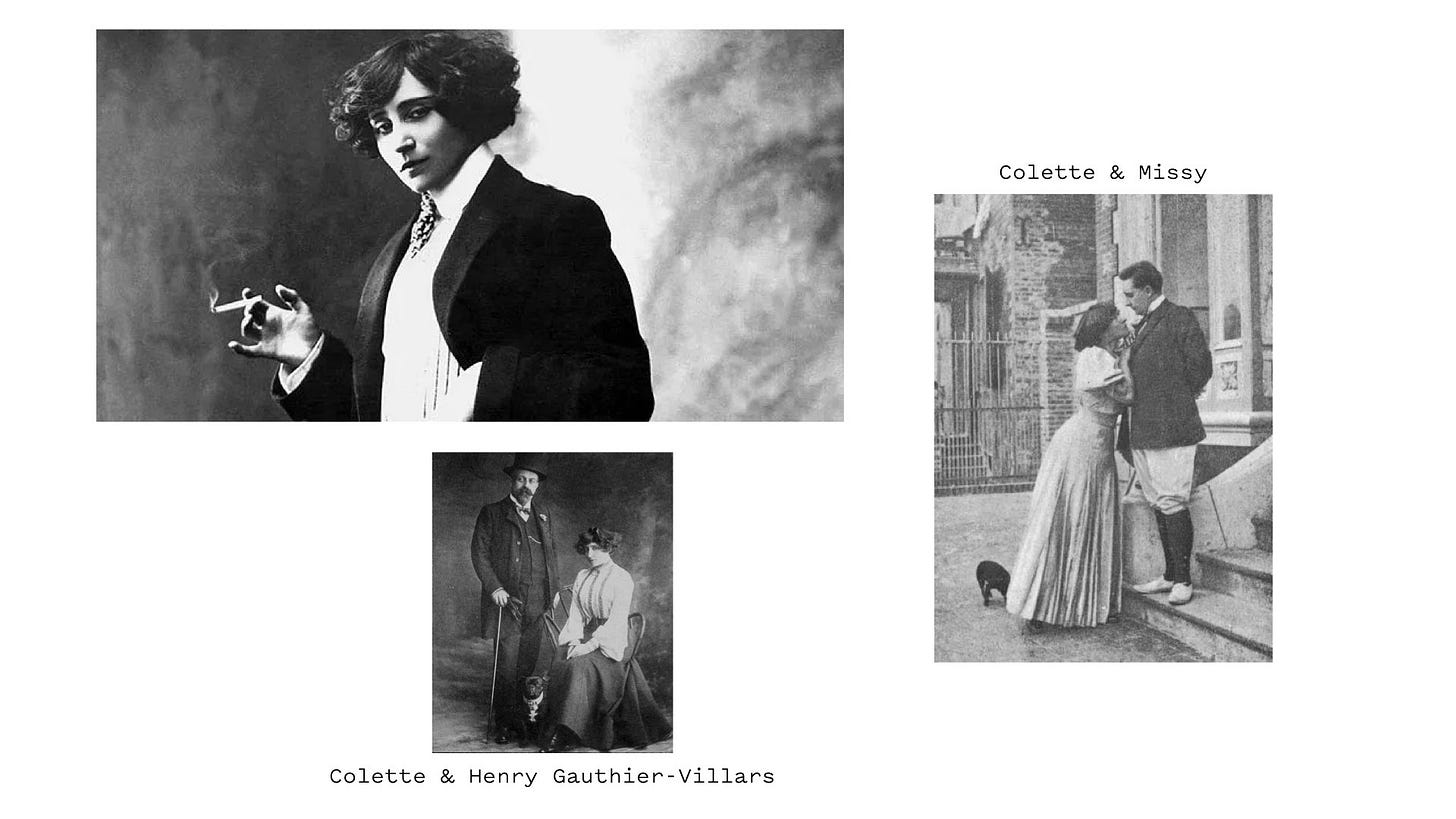

This was certainly the case for Colette, who moved to Paris in 1893. Despite being married to a man—Henry Gauthier-Villars who was traditional, untalented, and 14 years older than her—she started to embody a more evocative and androgynous identity in her new city. She began to work as a ghostwriter for her hack of a husband, and discovered she had real talent as an author.

Once she got rid of him—divorce, not murder—she began to explore a whole new world of intellectual stimulation. She had a series of rendezvous with several women, but only caused a literal riot in the streets outside Moulin Rouge with one. On January 3, 1907 (the specificity of this date gets me), Colette and her partner at the time, Mathilde de Morny, or “Missy”, kissed on-stage during a pantomime performance. People lost their minds.

They stayed together for another five years after the scandal. She then moved on to men many years her junior. These experiences were funneled into her writing, publishing her iconic Chéri in 1920 and Le Blé en Herbe in 1923, both about cougar behavior.

Around the time that Colette and Missy were smooching on stage, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas were meeting for their first date, a walk around the streets of Paris. (Literary Ladies Guide just recently wrote a great piece on the whole of Gertrude and Alice’s relationship, here). At this time, Gertrude was already established on the scene having published a variety of books and essays. She shared her salon at 27 rue de Fleurus with her brother Leo, which I love. The salon attracted all kinds of kinds, in large part due to their fabulous art collection including Matisse, Picasso, Man Ray—people would come over just to admire. It became a hub for the meeting of some incredible minds.

Over the years, Paris became a haven for the liberated, in part thanks to the example these women set. They were certainly New Women: catalysts and pioneers completely in charge of every aspect of their own lives, especially their literary ones.

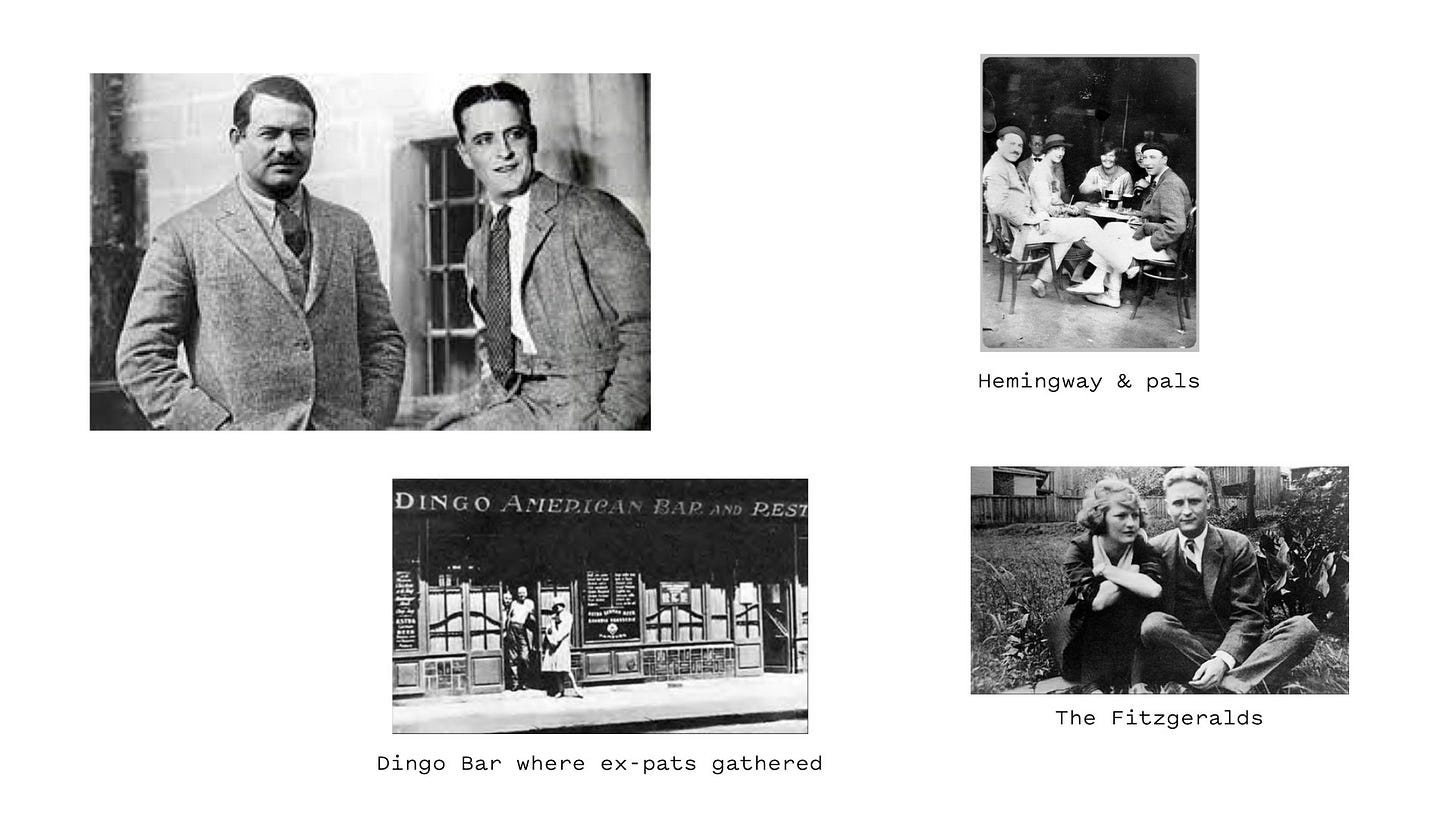

“You all are a lost generation”—a quote from Gertrude Stein that was bestowed upon the generation who came of age right after World War I, and more specifically the group of writers that cropped up in Europe around this time. Characterized by disillusionment, their work reflected the times.

Chief among them, our boys Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Hemingway moved to Paris with his wife Hadley in 1922, Fitz with Zelda in 1924. Hemingway wrote The Sun Also Rises and A Moveable Feast while in Paris, Fitz The Great Gatsby and Tender is the Night. This tumultuous bromance began at Dingo Bar in 1925, and they would go on to spend quite a lot of time together moving in same circle on the Left Bank, with Stein at the helm. But Hemingway’s macho persona and militant writing style, and Fitzgerald’s highbrow vibe and lyrical writing style made them perfect rivals—foils. Over the course of their friendship, they helped each other, judged each other, envied each other, and wrote scathing letters to and stories about each other. Despite the drama, there was reverence. They both understood they were in the presence of genius.

Another who understood this: Sylvia Beach, owner of Shakespeare and Company, when she read Ulysses by James Joyce. In 1920, writer Ezra Pound invited Joyce to visit Paris for a week. He stayed for 20 years.

The mammoth that is Ulysses had been rejected by publishers elsewhere, so Sylvia said she’s do it. Founded as part-bookstore, part-lending library, Shakespeare and Company was like a magnet, attracting this vast group of writers and artists, embodying the peak of Paris creativity. The publication of Ulysses caused both her bookstore’s and his career’s ascent to fame. And ironically, in a way, its demise as well. In 1941, a Nazi officer demanded that Beach sell him her last copy of Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. She refused. She was subsequently sent to the Vittel internment camp for 6 months, and had to close the doors, under her name at least, forever.

As the world emerged from WWII, Paris started to get its spark back. Once again, with a concentration of bookstores and publishing houses in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the Left Bank was where alllll the action was.

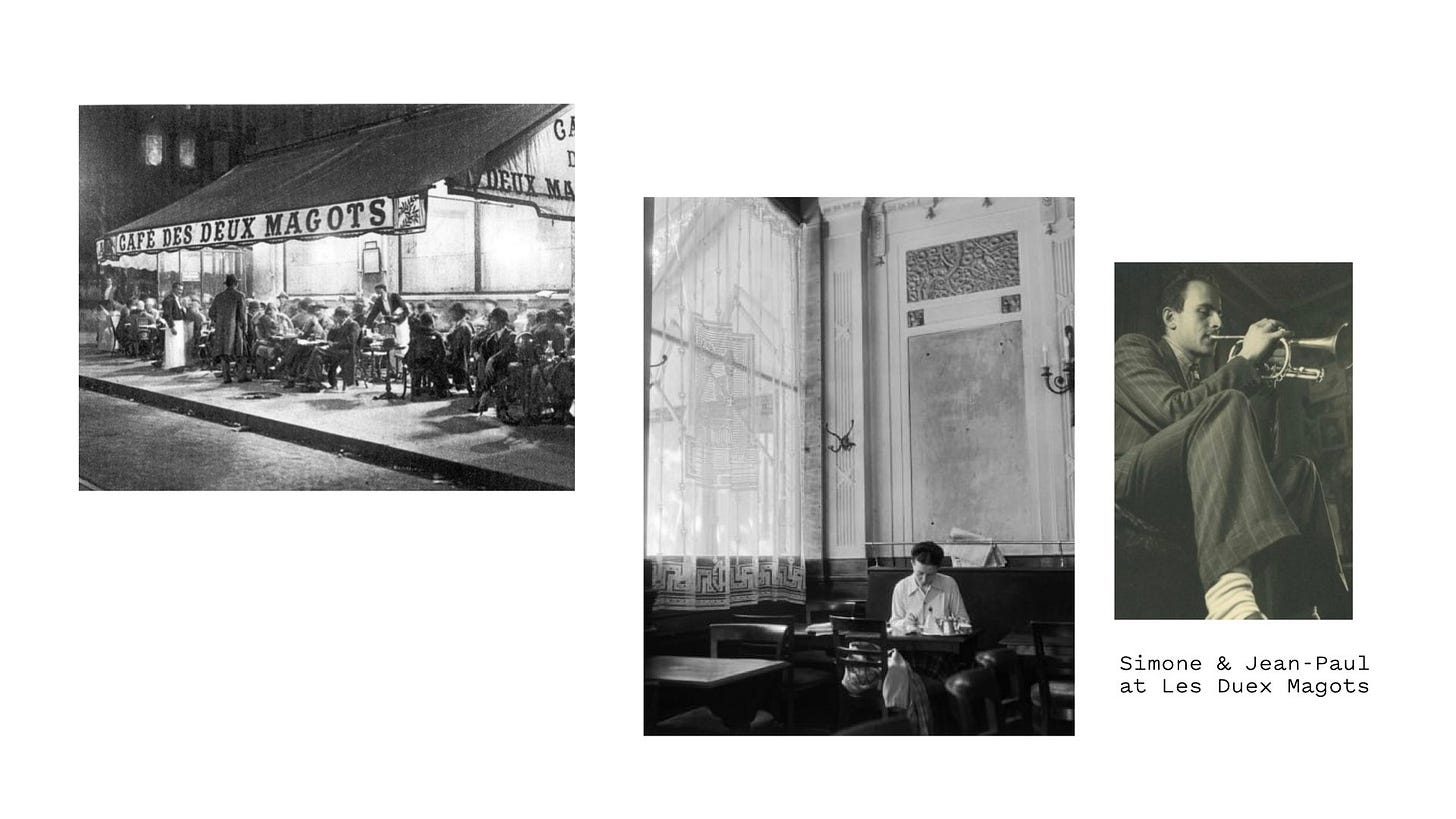

Writers congregated, contemplated, ideated in cafes. Three in particular: Brasserie Lipp, Les Duex Magots, Cafe le Flores—all on the corner of Boulevard Saint Germain and Rue de Rennes. We stayed at a cute hotel, Hôtel La Folie des Prés, a block away from this corner, and I swear I could feel it.

Les Duex Magots is where Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre held court. de Beauvoir was born in Paris in 1908 not far from the future action, right in the heart of the 6th arrondissement. Of her childhood, in Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, she said: "My father's individualism and pagan ethical standards were in complete contrast to the rigidly moral conventionalism of my mother's teaching. This disequilibrium, which made my life a kind of endless disputation, is the main reason why I became an intellectual."

She, too, was a New Woman. She went to the Sorbonne after university to continue studying philosophy, where she shaped the feminist ideas she’d go on to share with the world through her writing.

There she met Jean-Paul Sartre who would go on to be her partner for 50 years. She was vehemently against the institution of marriage. Which makes sense considering the book she’s most famous for, The Second Sex, rails against the patriarchy. In that book, she outlines how in a society where man is “default”, women became “other”, and therefore all that women are is considered in relation to men. At a hefty 832 pages, she examines so much, like how a lot of this inequity can be traced back to the differences of childhood experience and expectations of boys and girls. Girlhood is something she also explores in the recently, posthumously published Inseparable—a lovely read.

With marriage and its roles as a direct reflection of this society she’s outlined, she said: hard pass.

Jean-Paul Sartre is a philosopher in his own right and the founder of the school of existentialism. But in so many articles that I read, Simone is referred to as his partner first and a philosopher second, which she would absolutely loathe, so I’ll spend no more time on HER partner and philosopher.

Next door to Les Duex Magots at Cafe Le Flores, James Baldwin was often found writing. He arrived in Paris is 1948 after fleeing from Jim Crow America—”My journey, or my flight, had not been to Paris, but simply away from America.” He had a rocky start, spending Christmas of 1949 in jail, but quickly became a part of the world. Like many before him, he ultimately saw his time in Paris as one of self-discovery—removing himself from the oppression of America, to the comparative liberation of Paris, allowed him space to breathe and think and be. He was productive too, writing Giovanni's Room, Notes of a Native Son, and most of Go Tell It on the Mountain there.

Of Paris, James Baldwin said: "The arrogant indifference on the part of the Parisian, with its unpredictable effects on the traveler, which makes so splendid the Paris air, to say nothing whatever of the exhilarating effect it has on the Paris scene."

The arrogant indifference is somehow so appealing. Throughout history, Paris has been living its fabulous life, not giving a rip who people are, what they create, who they love, what they wear. That’s not to say it was perfect—nowhere is—but that it was conducive to a kind of magic that still lingers today.

I only scratched the surface here, if you can believe it. I hope you enjoyed!

This is so impressive! I love.